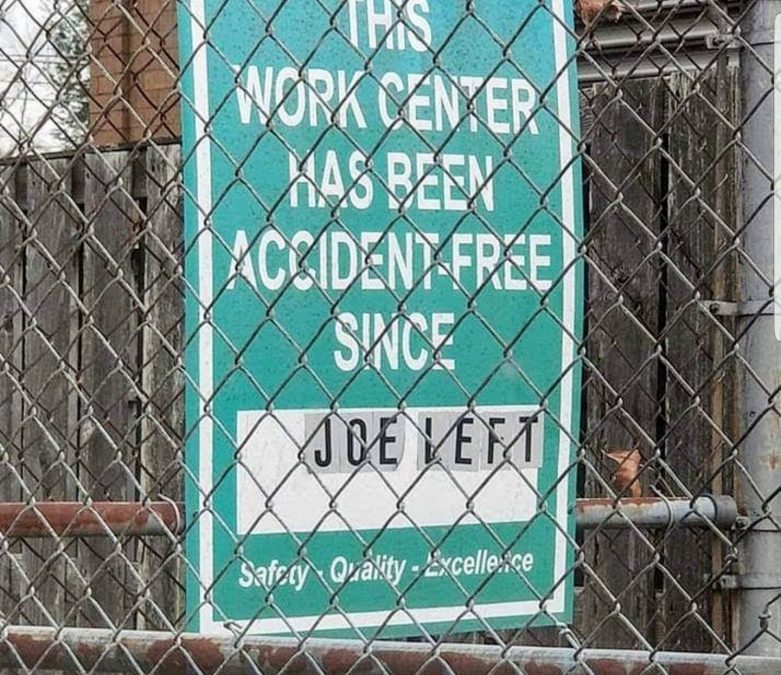

Almost everyone has worked with a Joe.

[Apologies to all of the Joes I know. What can I say? That’s the name of the guy in the meme.]

I’ve worked with Joe. I have clients who are struggling with Joe. I have been a part of root cause investigations in which one of the outcomes was terminating Joe’s employment.

Joe is what I light-heartedly refer to as a “frequent flier.” He is a repeat customer relative to workplace incidents, seeming to have an inordinate amount of bad luck or lousy timing, resulting in property damage, minor or major injuries and often, production or quality issues.

Joe feels like an accident waiting to happen.

Joe causes his team members and his supervisors and managers a lot of frustration and worry. Sometimes everyone tiptoes around Joe; other times it seems he needs to be supervised closely, or as his co-workers might say, “babysat.”

No one wants to see Joe get hurt –or worse– and any decent team member wants to see their work colleague safe and gainfully employed. Many of us have lost sleep over Joe.

Joe seems to be his own worst enemy.

So, what do we do about Joe?

In short, it’s time to get curious.

Research shows that the best leaders, and I will vouch for the best safety professionals, are profoundly curious people. The Generative Role of Curiosity … [Horstmeyer]

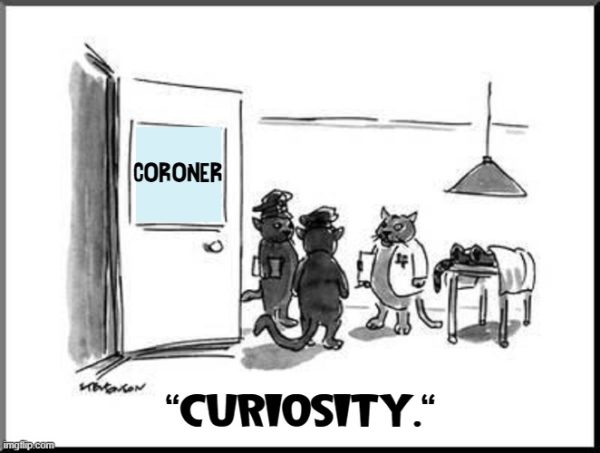

Or for a slightly less academic read, check out: Curiosity Didn’t Kill The Cat [Entrepreneur magazine, February 19, 2022]

Better for humans than felines!

What is it about curiosity?

Curiosity is the intellectual striving for knowing more in order to do better. It requires engagement and empathy and the willingness to ask questions without a pre-conceived sense of a correct answer.

It is easy to write Joe off, conclude that he is a lost cause, and give up. This often leads to progressive discipline, leading to termination. In a significant percentage of cases, it leads to just ignoring the problem or attempting to manage it, which is potentially far more risky, for both Joe and the organization.

We can do better.

As I said once to a group of supervisors during safety training —

“It’s simple, really, but not easy. Your gig is to figure out how to coach every single person on your team, knowing that they are as different from you as I am from you, or as different as your three kids are from one another. Or the kid down the street.”

When it comes to Joe, what does it look like to get curious?

It means asking about every workplace or personal factor we think may be influencing his performance. With a lack of defensiveness about the answers. Seeking solutions. Being mindful of The Blame Game, and avoiding it at all costs.

Real root cause analysis, asking the question “why?” — it’s not for the faint of heart. It’s going to involve what I like to call a bit of Essential Pain.

Because inevitably, the organization is responsible, at least to some degree, for Joe. It’s not all about Joe, and blaming Joe, while convenient, is simplistic. And it doesn’t improve how the organization functions.

Let’s face it. No one heads into work each day intending to get hurt, or have a forklift fender bender. That includes Joe.

So where is the gap with Joe?

- Has he had the right kind of coaching?

- Is he in a role that fits his skill set and abilities?

- What makes Joe tick? In other words, what motivates his best performance? (And before you say his paycheck, know that that is rarely a significant motivator.)

- More delicately, perhaps, does Joe have something going on outside of work that’s impacting his performance?

Have you had a heart-to-heart with Joe?

I am shocked sometimes to find how many people are talking about Joe without actually talking to Joe.

Once, much earlier in my career, I recall losing my patience with someone I worked with and finally throwing my hands up in the air. I’d found him, again, in the shop, using a grinder, without eye protection. —

“Please, tell me! What can I do to get you to wear your safety glasses!?”

While my delivery was not smooth, it did open the door to a conversation — although I admit it was initially unpleasant, and perhaps at a higher than office-appropriate decibel level. We did find some answers. Some were about the actual safety glasses, which left something to be desired in terms of their fit and function.

But some were about the very nature of that particular employee. He had reached a certain age –something I empathize with more at 55 than I suspect I did at 35– and he reflexively removed his glasses when he needed to see something up close, setting them down and sometimes misplacing them.

At that time, progressive safety glasses and “cheater” safety glasses were not widely available, but we did manage to find a good solution.

This was a good employee. His motivation for getting a better look was because he took pride in his work. He was also not wild about not being able to see as well as he used to. There was a lot going on; there almost always is.

Both of us feeling a bit better about our impasse, and with several solutions in place, I asked the employee–

“Okay, what do you want me to do if I catch you again without your safety glasses on?”

“Write me up. That will get my attention. I can’t afford to lose my job. Trust me, my wife will straighten me out.”

I never had to do that. It gave me giddy pleasure, catching him getting it right. Sometimes I would act overboard about, gesturing to my own safety glasses, and giving him a big thumbs-up and a smile. It was a win/win. Perfectly executed? No, but hard conversations rarely are.

Sometimes Joe needs to go. I don’t deny that. But every time an employee is terminated, even when it feels we’ve done everything we could, it is a loss.

Is it possible there’s more questions to ask that could hold the solution?

Please ask. Joe is counting on it. So is your organization.